Progressive Supranuclear Palsy (PSP) is a rare degenerative brain disorder that affects movement, control of walking and balance, vision, speech, and cognition. Progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP) represents the most common form of atypical Parkinsonism with a prevalence of 6.5 cases/1.000.000 people. The neuropathological hallmark of PSP is a biochemical alteration in the tau protein, which results in a neurodegeneration and gliosis in the basal ganglia, brainstem, prefrontal cortex and cerebellum.

|

| Progressive supranuclear palsy |

The disorder's name refers to the disease worsening (progressive) and causing weakness (palsy) by damaging the brain above nerve cell clusters called nuclei (supranuclear). These nuclei predominantly control eye movement.

The 5 minute video below is good for an overview of symptoms and diagnosis.

Etiology

The cause of progressive supranuclear palsy is unknown. Available evidence collectively suggests a possible role of advanced age, low education, metal exposure and consumption of well-water.

The signs and symptoms that appear with PSP are caused by the deterioration of brain cells in the brainstem, cerebral cortex, cerebellum, and basal ganglia. These areas are important for the control of body movements (midbrain) and thinking (frontal lobe).

This deterioration is due to the abnormal amount of protein called tau. Research is focused on genes that may predispose an individual to developing the disease, as well as ways to prevent clumping of tau in treating the disorder.

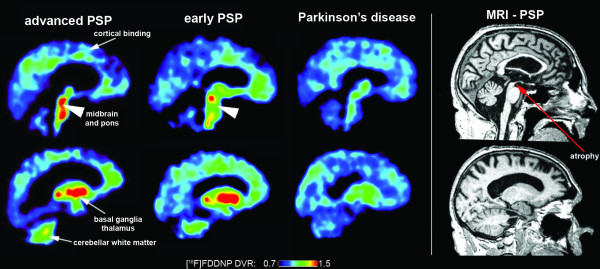

Tau ligand binding patterns in progressive supranuclear palsy

Epidemiology

- PSP is the most common atypical parkinsonian disorder.

- It is considered as having an approximate prevalence of 5–6.5 per 100,000.

- Higher PSP prevalence reported from Japan, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom. This higher prevalence could be related to the aging of population, increased general awareness of the condition, inclusion of various disease phenotypes and also the fact that recruitment occurred within a government-based program in Japan that provides support for rare disorders such as PSP.

- In some non-selected community-based brain autopsy series 3–5% of cases with no or minimal clinical findings have showed PSP pathologies suggesting that the true prevalence of PSP is probably much higher.

- PSP prevalence increases with age and shows no gender predominance

- The annual incidence rate of progressive supranuclear palsy ranged from 0.3 to 0.4 per 100,000 - 1.1 per 100,000. The greater incidence (found in the latter studies) is likely due to better case ascertainment with increased recognition of the disorder and its clinical variants.

- The annual incidence increases with age from 1.7 cases per 100,000 at ages 50 to 59 years to 14.7 per 100,000 at 80 to 89 year.

- The mean age of onset for progressive supranuclear palsy is approximately 65 years, which is older than in idiopathic Parkinson disease.

- Virtually no cases of autopsy-confirmed progressive supranuclear palsy have been reported in patients younger than age 40 years.

Pathophysiology

- PSP belongs to the family of tauopathies.

- Abnormalities in the protein tau lead to damage in both cortical and subcortical areas of the brain.

- The defining histopathologic feature of progressive supranuclear palsy is an intracerebral aggregation of the microtubule-associated protein tau with preferential involvement of the subthalamic nucleus, pallidum, striatum, red nucleus, substantia nigra, pontine tegmentum, oculomotor nucleus, medulla, and dentate nucleus.

- Definite diagnosis of progressive supranuclear palsy currently requires neuropathological examination.

Clinical Presentation

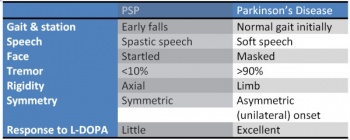

Clinical features of PSP include early postural instability with recurrent falls (mostly backwards), speech problems, swallowing difficulties, visual dysfunctions (vertical supranuclear gaze palsy), pseudobulbar palsy, bradykinesia, axial rigidity and neuropsychological deficits.Falls represent the main cause of reduced independence, morbidity and mortality in this disorder

- Movement disorders

- Bradykinesia, with marked micrographia, are primary features of parkinsonism present in all types of progressive supranuclear palsy.

- Rigidity in patients with progressive supranuclear palsy is usually more apparent in axial than limb muscles, especially the neck and upper trunk.

- On examination, it can be demonstrated by resistance to passive movement of the neck. There can be dystonia of the neck, typically retrocollis.

- The face of patients with progressive supranuclear palsy is often stiff, immobile, and deeply furrowed (the look of surprise) also due to dystonia.

- About one-third of patients with progressive supranuclear palsy develop pyramidal signs, including hyperreflexia and Babinski signs.

- A jaw jerk and other frontal release signs (primitive reflex reflecting frontal lobe pathology) can be present.

- Spastic dysarthria, dysphonia, and dysphagia can be profound in the middle to later stages of the disease.

2. Postural Instability and Falls

- Stiff and broad-based gait, with an inclination to have their knees and trunk extended (as opposed to the flexed posture of idiopathic Parkinson disease), and arms slightly abducted.

- Instead of turning en bloc, as seen in Parkinson disease, they tend to pivot quickly, which further increases their risk of falls. This is sometimes referred to as the "drunken sailor gait." When they fall, it is usually backward due to a lack of postural reflexes.

- As the disease continues to progress people have increased difficulty with movement (many movements become slow and clumsy)

- Gait difficulties, each step becomes slow and deliberate with broad-based steps.

- Eventually, most PSP patients require wheelchair assistance due to balance issues.

3. Visual problems. All of these abnormalities with the eyes can lead to blurry vision, double vision, light sensitivity, and staring gaze.

- Abnormal eye movements develop several years after other movement dysfunctions and often present as an inability to move the eyes up and down.

- Difficulty opening and closing the eyelids, infrequent blinking, and retraction of the eyelids.

- In very advanced stages the eyes may not move at all.

4. Swallowing (dysphagia) As the dysphagia becomes more severe, aspiration pneumonia becomes a concern. Counselling on food preparation and swallowing to avoid aspiration is indicated in many

5. Speech (dysarthria).

6. Sleep Disturbances. Early or late insomnia and difficulties in maintaining sleep. Marked rigidity may result in the inability to remain comfortable in bed, further contributing to sleep complaints. Rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder (RBD) is infrequently associated with progressive supranuclear palsy (a negative finding, similar to preserved olfaction, can be helpful in differentiating progressive supranuclear palsy, a tauopathy, from Parkinson disease and multiple system atrophy).

7. Personality, behaviour and cognitive changes. Personality changes are often presented as apathy (loss of interest and enthusiasm). Cognitive changes present as difficulties with cognition, attention, planning, and problem solving.

Diagnostic Procedures

- There are no known laboratory tests or imaging techniques that can specifically diagnose PSP at this time. A diagnosis is generally made using the patient history in combination with both physical and neurological scans.

- Often times an MRI will demonstrate changes in activity in affected cortical areas, as well as shrinkage and plaque development due to neuronal loss in the basal ganglia, cerebellum, and brainstem. While no feature on MRI or functional imaging studies is entirely specific for progressive supranuclear palsy, the “hummingbird sign” is often present, in which the shape of the rostral midbrain atrophy on mid-sagittal images looks like a hummingbird.

- Symptoms of PSP often mimic other diseases and movement disorders, with the development of cardinal signs varying widely in developmental timing and severity between cases.

- Diagnosis of PSP should be considered in all patients presenting with parkinsonism not responding to levodopa, postural instability with falls, executive dysfunction, dysarthria, and, importantly, eye movement abnormalities.

Management and Interventions

The management of the cognitive, motor, and gait aspects of progressive supranuclear palsy is challenging, and the treatment for individuals suspected to have progressive supranuclear palsy remains symptomatic and supportive, with ongoing clinical trials striving to identify disease-modifying therapies often targeting the underlying tau pathology. There are no effective medical or surgical treatments for PSP.

There is little known long term benefit to drug agents in this disease, despite its parkinsonian presentation. Occasionally, bradykinesia and stiffness of gait can be altered transiently with levodopa, and botulinum toxin often can decrease involuntary eye closing and results in no long term effects. Non-drug treatments for PSP can include assistive walking devices for the prevention of falls (often include counterweights for extensor postures). Often people are prescribed prism glasses that treat the patient’s decreased ability to look down, allowing better visual input for balance and walking. There is evidence of exercise through physiotherapy for the maintenance of strength, coordination, and balance in these patients.

Differential Diagnosis

PSP is often misdiagnosed as it is quite rare. The differential diagnosis of progressive supranuclear palsy includes

- corticobasal ganglionic degeneration (CBGD),

- Parkinson disease,

- Pick disease.

- Microvascular disease of the brainstem and tumors of the midbrain area can mimic progressive supranuclear palsy.

- Whipple disease,

- mitochondrial myopathies,

- Wilson disease

- Adult-onset Niemann-Pick disease.

- With the bulbar onset of symptoms, myasthenia gravis and Motor Neurone Disease should be included in the differential diagnosis.

- Alzheimer’s Disease

- Apraxia and Related Syndromes

- Multisystem Atrophy (MSA) of the parkinsonian type

- Syringomyelia

Outcome Measures

- Progressive supranuclear palsy rating scale (PSPRS)

- Progressive Supranuclear Palsy Quality of Life scale (PSP-QoL)

- Neuroprotection in Parkinson Plus Syndromes–Parkinson Plus Scale (NNIPPS-PPS)[12]

- Berg Balance Scale (BBS)

- 6 Minute Walk Test (6MWT)

Physiotherapy

Studies confirms the importance of an aerobic, multidisciplinary, motor-cognitive, goal-based and intensive approach for the rehabilitation of patients suffering from such a complex disease as PSP.

- The potential value of physical therapy is of increasing interest, particularly given evidence of benefit for individuals with Parkinson disease, and a recent trial showed improvement in the Progressive Supranuclear Palsy Rating Scale (PSPRS)

- Physical therapy with particular attention to balance training and “learning to fall” can minimize the potential for injury and provide patients with tools for maneuvering after a fall has occurred.

- The use of a walker is often necessary for safe ambulation and transfers. At late stages, even using a walker is not enough to maintain balance, and patients may need to use a wheelchair exclusively.

Since there is no medication available to treat this condition, patients are often referred to physiotherapy in order to manage their symptoms. Most physiotherapy interventions for PSP include an exercise regimen that consists of

- Aerobic exercises

- Transfer/balance training

- Gait training

- Weighted tool can be used to prevent backward falls

- Flexibility training

- Intensive routines

- Goal-oriented tasks

- Visual tracking

- Prism lenses sometimes used to further train gaze

- Motor-cognitive exercises

The study recommends future trials using methods such as the Consensus on Exercise Reporting Template (CERT) to provide a comprehensive description of exercise and physical activity interventions in patients. An exercise program following these guidelines is recommended for about 1-2 hours a day, 5 days a week, in order to show any significant improvements.

Concluding Remarks

- Unlike typical Parkinson disease, falls begin within the first year of progressive supranuclear palsy, and by year 3, they are common unless precautions are taken to prevent them.

- Downgaze is affected before upgaze, whereas; lateral eye movements are usually preserved in progressive supranuclear palsy.

- Apathy seems to predominate over other neurobehavioral abnormalities in progressive supranuclear palsy.

- Patients with progressive supranuclear palsy develop frontal cognitive impairment.

- The pathology of progressive supranuclear palsy is characterized by widespread neurodegeneration associated with tau protein deposition in subcortical regions.

- Studies confirms the importance of an aerobic, multidisciplinary, motor-cognitive, goal-based and intensive approach for the rehabilitation of patients suffering from PSP.

- The first therapeutic step in progressive supranuclear palsy is identifying and prioritizing the symptoms that can be treated.

0Comments