Knee replacement, also called knee arthroplasty or total knee replacement, is a surgical procedure to resurface a knee damaged by arthritis.

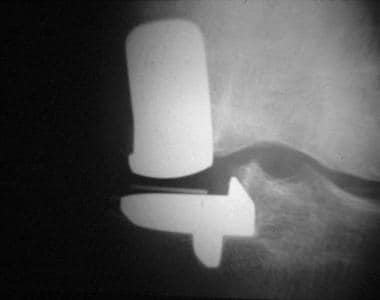

The primary indication for total knee arthroplasty (TKA; also referred to as total knee replacement [TKR]) is relief of significant, disabling pain caused by severe arthritis. (See the image below.)

|

| Total knee arthroplasty. Radiograph demonstrating posttraumatic osteoarthritis. |

Preparation

Anesthesia

TKA may be performed with the patient under regional or general anesthesia. Which of these is used depends partly on the medical condition of the patient, though cardiovascular outcomes, cognitive function, and mortality rates associated with regional and general anesthesia have not been proved to be significantly different.

Patients who have epidural anesthesia have been shown to develop fewer perioperative deep vein thromboses (DVTs). Whether this has an overall positive benefit for the patient is not known.

Equipment

Types of TKA prostheses include the following:

Fixed bearingMedial pivot

Rotating platform and mobile bearing

Posterior cruciate ligament (PCL)-retaining

PCL-substituting

Patient evaluation

Preoperative medical evaluation of the patient includes the following:

Medical evaluation - Patients must have good cardiopulmonary function to withstand anesthesia and to cope with a blood loss of 1000-1500 mL over the perioperative period; routine preoperative electrocardiography should be performed on elderly patientsLaboratory studies - These include (1) complete blood count (CBC), (2) erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), (3) serum electrolytes, (4) renal function studies, (5) prothrombin time (PT) and activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT), (6) urinalysis, and (7) urine culture

Imaging studies - These include (1) standing anteroposterior (AP) view, (2) lateral view, (3) patellofemoral (skyline) view, (4) long leg radiographs (to assess malalignment), and (5) standing radiographs with the knee in extension or in 45º of flexion (Rosenberg view)

Antibiotics and antithromboembolic devices

Antibiotics and antithrombotic prophylaxis are administered approximately 30 minutes before the incision is made. Mechanical antithromboembolic devices (eg, stockings, foot pumps) are used intraoperatively.

Technique

TKA is performed as follows:

The knee joint is usually approached anteriorly through a medial parapatellar approach, though some surgeons use a lateral or subvastus approachBone cuts in the distal femur are made perpendicular to the mechanical axis, typically using an intramedullary alignment system (which is then checked against the center of the hip)

The proximal tibia is cut perpendicular to the mechanical axis of the tibia using either intramedullary or extramedullary alignment rods

Restoration of mechanical alignment is important to allow optimum load sharing and prevent eccentric loading through the prosthesis

Sufficient bone is removed so that the prosthesis recreates the level of the joint line

Ligaments around the knee that are contracted because of preoperative deformity are carefully released in a stepwise fashion

Patellofemoral tracking is assessed with trial components in situ and balanced if necessary with a lateral release or medial reefing procedure

If the patellofemoral joint is significantly diseased, it can be resurfaced with a polyethylene button

Once the definitive prosthetic components have been selected, they are cemented into place with polymethyl methacrylate cement

If an uncemented system is being used, press-fit and bony ingrowth provide fixation of the component

Foot pulses are checked at the end of the procedure

Postoperative care

The patient undergoes recovery and is usually observed for a 24-hour period in a high-dependency ward. Adequate hydration and analgesia are essential in this time of high physical stress. Analgesia is provided through continuation of the intraoperative epidural, patient-controlled intravenous analgesia, or oral analgesia. Cryotherapy is used to reduce postoperative swelling and pain.

At this early stage, the patient begins knee movement, sometimes using a continuous passive motion (CPM) machine and exercises. These are continued under the supervision of a physiotherapist until discharge.

Drains are usually removed within 24 hours, and the patient is encouraged to walk on the second postoperative day. Continual improvement is generally observed, and discharge occurs in 5-14 days. Thromboembolism prophylaxis is often continued at home for a period of time.

Background

Total knee replacement (TKR) in some form has been practiced for more than 50 years, but in the earleist days of the procedure, the complexities of the knee joint were not fully understood. Because of this, TKR initially was not as successful as Sir John Charnley's artificial hip. However, dramatic advancements in the knowledge of knee mechanics have led to design modifications that appear to be durable.

Significant advances have occurred in the type and quality of the metals, polyethylene, and ceramics used in the prosthesis manufacturing process, leading to improved longevity. As with most techniques in modern medicine, more and more patients are receiving the benefits of total knee arthroplasty (TKA). Approximately 130,000 knee replacements are performed every year in the United States.

In the 1860s, Fergusson reported performing a resection arthroplasty of the knee for arthritis. Verneuil is thought to have performed the first interposition arthroplasty using joint capsule. Other tissues were subsequently tried, including skin, muscle, fascia, fat, and even pig bladder.

The first artificial implants were tried in the 1940s as molds fitted to the femoral condyles following similar designs in the hip. In the next decade, tibial replacement was also attempted, but both designs had problems with loosening and persistent pain.

Combined femoral and tibial articular surface replacements appeared in the 1950s as simple hinges. These implants failed to account for the complexities of knee motion and consequently had high failure rates from aseptic loosening. They were also associated with unacceptably high rates of postoperative infection.

In 1971, Gunston importantly recognized that the knee does not rotate on a single axis like a hinge; rather, the femoral condyles roll and glide on the tibia with multiple instant centers of rotation. His polycentric knee replacement had early success with its improved kinematics over hinged implants but was ultimately unsuccessful because of inadequate fixation of the prosthesis to bone.

The highly conforming and constrained Geomedic knee arthroplasty introduced in 1973 at the Mayo Clinic ignored Gunston's work, and a kinematic conflict arose. Other designs followed, either following Gunston's principle in attempting to reproduce normal knee kinematics or allowing a conforming articulation to govern knee motion.

The total condylar prosthesis was designed by Insall at the Hospital for Special Surgery in 1973. This prosthesis concentrated on mechanics and did not try to reproduce normal knee motion. In 1993, Ranawat et al reported a rate of survivorship of 94% at 15 years of follow-up, which is the most impressive reported to date.

The component was subsequently altered to artificially introduce normal kinematics so as to improve the component's range of motion (ROM). At the same time, a prosthesis with more natural kinematics was developed at the Hospital for Special Surgery, relying on the retained cruciate ligaments to provide knee motion.

The argument over whether knee ligaments should be preserved or sacrificed continues to this day. Long-term follow-up studies do not show any significant differences, though gait appears to be less abnormal if ligaments are preserved, especially when walking up and down stairs. One theoretical way of incorporating normal kinematics and maximal conformity is to use mobile tibial bearings. Midterm follow-up studies of these prostheses have shown encouraging results.

Cemented TKR procedures have been the criterion standard for TKA, but uncemented designs with bioactive surfaces (eg, hydroxyapatite) have shown promising midterm results (see the image below).

|

| Total knee arthroplasty. Electromicrograph showing incorporation of bone (red) onto surface of hydroxyapatite. |

Indications

The primary indication for TKA is to relieve pain caused by severe arthritis. The pain should be significant and disabling. Night pain is particularly distressing. If dysfunction of the knee is causing significant reduction in the patient's quality of life, this should be taken into account.

Correction of significant deformity is an important indication but is rarely used as the primary indication for surgery. Roentgenographic findings must correlate with a clear clinical impression of knee arthritis. Patients who do not have significant loss of joint space tend to be less satisfied with their clinical result after TKA. All conservative treatment measures should be exhausted before surgery is considered.

Knee replacement has a finite expected survival that is adversely affected by activity level.

Generally, it is indicated in older patients with more modest activities. It is also clearly indicated in younger patients who have limited function because of systemic arthritis with multiple joint involvement. Young patients requesting knee replacement, especially those with posttraumatic arthritis, are not excluded by age but must be significantly disabled and must understand the inherent longevity of joint replacement.

Rarely, severe patellofemoral arthritis (see the image below) may justify arthroplasty on the grounds that the expected outcome of arthroplasty is superior to that of patellectomy. Isolated patellofemoral replacement still is undergoing clinical investigation.

|

| Total knee arthroplasty. Lateral radiograph demonstrating severe patellofemoral osteoarthritis. |

Deformity can sometimes become the principal indication for knee replacement in patients with moderate arthritis when flexion contracture or varus or valgus laxity is significant. In such cases, a more constrained prosthesis is often required, leading to greater technical difficulty in surgery and greater uncertainty regarding long-term survival.

Contraindications

Absolute contraindications for TKA include the following:

Knee sepsisA remote source of ongoing infection

Extensor mechanism dysfunction

Severe vascular disease

Recurvatum deformity secondary to muscular weakness

Presence of a well-functioning knee arthrodesis

Relative contraindications include medical conditions that preclude safe anesthesia and the demands of surgery and rehabilitation. Other relative contraindications include the following:

Skin conditions within the field of surgery (eg, psoriasis)Past history of osteomyelitis around the knee

Neuropathic joint

Obesity

Technical Considerations

Anatomy

Movement of the knee joint can be classified as having six degrees of freedom, comprising three translations and three rotations, as follows:

Translations - (1) Anterior/posterior, (2) medial/lateral, and (3) inferior/superiorRotations - (1) Flexion/extension, (2) internal/external, and (3) abduction/adduction

Movements of the knee joint are determined by the shape of the articulating surfaces of the tibia and femur and the orientation of the four major ligaments of the knee joint. The anterior cruciate ligament (ACL), the posterior cruciate ligament (PCL; see the image below), the medial collateral ligament (MCL), and the lateral collateral ligament (LCL) serve as a four-bar linkage system.

|

| Total knee arthroplasty. Sagittal MRI showing anterior and posterior cruciate ligaments. |

Knee flexion/extension involves a combination of rolling and sliding called femoral rollback, which is an ingenious way of allowing increased ranges of flexion. Because of asymmetry between the lateral and medial femoral condyles, the lateral condyle rolls a greater distance than the medial condyle during 20º of knee flexion. This causes coupled external rotation of the tibia, which has been described as the screw-home mechanism of the knee that locks the knee into extension.

Medial and lateral collateral ligaments

The primary function of the MCL is to restrain valgus rotation of the knee joint, with its secondary function being control of external rotation. The LCL restrains varus rotation and resists internal rotation.

Anterior cruciate ligament

The primary function of the ACL is to resist anterior displacement of the tibia on the femur when the knee is flexed and control the screw-home mechanism of the tibia in terminal extension of the knee. A secondary function of the ACL is to resist varus or valgus rotation of the tibia, especially in the absence of the collateral ligaments. The ACL also resists internal rotation of the tibia.

Posterior cruciate ligament

The main function of the PCL is to allow femoral rollback in flexion and resist posterior translation of the tibia relative to the femur. The PCL also controls external rotation of the tibia with increasing knee flexion. Retention of the PCL in TKR has been shown biomechanically to provide normal kinematic rollback of the femur on the tibia. This also is important for improving the lever arm of the quadriceps mechanism with flexion of the knee.

Patellofemoral joint

Movement of the patellofemoral joint can be characterized as gliding and sliding. During flexion of the knee, the patella moves distally on the femur. This movement is governed by the attachments of the patellofemoral joint to the quadriceps tendon, the ligamentum patellae, and the anterior aspects of the femoral condyles. The muscles and ligaments of the patellofemoral joint are responsible for producing extension of the knee.

The patella acts as a pulley in transmitting the force developed by the quadriceps muscles to the femur and the patellar ligament. It also increases the mechanical advantage of the quadriceps muscle relative to the instant center of rotation of the knee.

Mechanical axis

The mechanical axis of the lower limb is an imaginary line through which the weight of the body passes. It runs from the center of the hip to the center of the ankle through the middle of the knee. This axis is altered in the presence of deformity and must be reconstituted at surgery, which allows normalization of gait and protects the prosthesis from eccentric loading and early failure.

See Knee Joint Anatomy for more information.

Procedural planning

A number of operative procedures should be considered in patients with degenerative disease of the knee. Arthroscopic debridement is sometimes indicated in mild degenerative joint disease with mechanical symptoms and recurrent persistent effusions. Proximal tibial valgus osteotomy should be reserved for patients with medial tibiofemoral compartment disease, stable collateral ligaments, and a correctable varus deformity of the knee joint (see the image below).

|

| Total knee arthroplasty. Radiograph demonstrating proximal tibial valgus osteotomy created to offload medial compartment of knee. |

Similarly, a distal femoral varus osteotomy can be considered for patients with lateral tibiofemoral compartment disease, stable collateral ligaments, and a valgus deformity of the knee joint (see the image below).

|

| Total knee arthroplasty. Radiograph demonstrating distal femoral varus osteotomy. |

These procedures restore the mechanical axis of the lower limb and offload the diseased compartment. Proximal tibial valgus osteotomy and distal femoral varus osteotomy are generally reserved for young high-demand patients because of concerns about the durability of TKA in this patient group.

|

| Total knee arthroplasty. Radiograph demonstrating medial unicompartmental replacement. Note relative preservation of lateral joint compartment. |

A prospective, randomized, controlled trial in England compared unicompartmental knee replacement with TKA over 8, 10, 12, and 15 years of follow-up. At 5 years, the number of failures were equal in the two groups. At 15-year follow-up, the survivorship rate was 89.8% for unicompartmental knee replacement and 78.7% for TKA. Four of the unicompartmental knees failed, and six of the TKA knees failed. Newman et al determined from their findings that the results of their study justify increased use of unicompartmental replacement.

Arthrodesis or fusion of the knee is rarely performed but should be considered in patients with chronic sepsis, younger patients with tricompartmental disease (eg, following trauma) who require stability and durability, and patients with deficient extensor mechanisms. TKA is performed in patients with symptomatic advanced degenerative changes in one or more compartments of the knee joint.

Outcomes

A randomized controlled trial by Batailler et al (N = 118) assessed survival rates, clinical outcomes, and radiologic results of TKA with either cemented tibial and femoral components (n = 59) or a hybrid approach with uncemented femoral components and cemented tibial components (n = 59). [10] Patients were between the ages of 50 and 90 years, underwent primary TKA for osteoarthritis without a history of open knee surgery, and were followed for a minimum of 10 years. No significant differences were found between cemented TKA and hybrid TKA with respect to survivorship, complication rate, clinical scores, or radiologic signs of loosening.

A study of 118 elderly (>65 y) female patients undergoing TKA by Kwon et al found that underweight patients had poorer clinical outcomes than those with a normal body mass index (BMI), though the two groups did not differ significantly with regard to postoperative complications.

0Comments