Hepatitis D is a viral infection caused by the hepatitis D virus (HDV) which affects the liver. HDV was identified in 1977 in patients with chronic hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection. Hepatitis D is also known as “delta hepatitis”. Hepatitis D infection only occurs in people who are infected with the HBV.

Symptoms

Most of the people with HDV infection remain symptomless; however, some patients may show an increase in severity of their existing HBV infection symptoms. Common symptoms include fatigue, joint pain, abdominal pain, yellowing of eyes or skin, vomiting, and dark urine.

Incubation Period

The incubation period of HDV infection is 14-60 days. However, peak infection possibly occurs just before the onset of acute illness, when particles holding delta antigen are immediately detected in the blood stream. After onset, virus concentration falls quickly to low or untraceable levels.

Pathogenesisand Transmission

HDV is hepatotropic in nature. Replication of virus within hepatocytes leads to cytotoxicity and liver damage. Hepatocellular necrosis and inflammation which take place due to HDV infection show similarity to the pathology of other acute and chronic viral hepatitis. HDV can spread in blood via transfusion, semen and vaginal secretions, needlestick injury, and intravenous drug supplies. There are rare chances of transmission from mother to child.

Etiologyand Epidemiology

HDV infection can cause an acute (short-term) or chronic (long-term) inflammatory activity which is manifested generally via parenteral route. It replicates autonomously within hepatocytes, but requires hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) for proliferation. Hepatic cell death takes place due to direct cytotoxic effects of HDV or a host-mediated immune response. Perinatal transmission is uncommon in case of HDV infection. Blood transfusions and intravenous drug administration are the common risk factors.

It is projected that worldwide 5% of HBsAg positive people are coinfected with HDV. Mediterranean region, certain parts of Asia and Africa, and some regions in southern America are among those with highest prevalence of HDV infection.

Pathophysiology

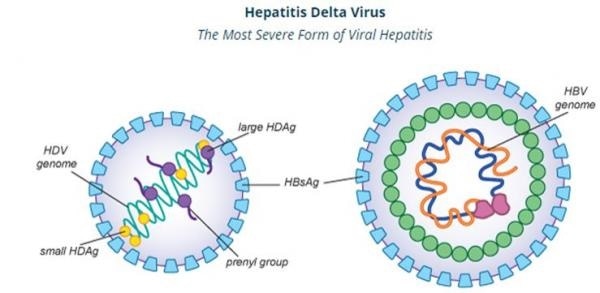

HDV comprises of an RNA genome, hepatitis D antigen (HDAg) along with a lipoprotein envelope (from HBV). HDAgs are of two types according to their sizes: long and short. Viral replication takes place in hepatocytes. The short HDAg initiates viral replication through direct binding to the HDV RNA, the long one guides viral assembly as well as inhibits viral replication. The virus gets completely assembled after the integration of HBV envelope, subsequently it is released.

Helper function required by HDV from HBV is synthesis of HBsAg. HDV requires HBsAg for virion assembly.The HDV nucleoprotein complex formed in the nucleus, and discharged into the cytoplasm, is covered by HBsAg to complete virion morphogenesis. The HBsAg envelope of the HDV virion is crucial for cellular attachment, and for the proliferation of HDV to other hepatocytes.

Hepatitis D

Types of Infection

There are two major patterns of infection: HDV coinfection and superinfection.

Simultaneous occurrence of HDV and HBV is termed as coinfection. The resultant infection is usually self-limiting and acute in nature. Incubation period for acute hepatitis D is approximately up to 2 months. Coinfections with HDV and HBV can grow into chronic HDV infections in about 5% of the patients suffering from coinfection.

When the patient is a chronic carrier of HBV, and is further infected with HDV, it is termed as superinfection. Approximately 80% of the patients encountering this phenomenon suffer from chronic hepatitis D infection later. Superinfection may also result into fulminant viral hepatitis, which is more commonly seen in the patients with HDV infections compared with those with other types of hepatitis. The mortality rate of fulminant hepatitis is quite high. Liver cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma are also reported in a relatively high number of patients having chronic hepatitis D. By and large, HDV infections have mortality rate of up to 20%, which is much higher than that of HBV infections.

Prevention and Management of HDV

Prevention of HDV infection depends on the prevention of HBV. In order to reduce the chances of parenteral transmission, one should avoid sharing intravenous drug needles or supplies. Practicing safe sex is advised. As far as the treatment is concerned, there are limited choices for delta hepatitis infection, and optimal treatment is yet to be identified. Pegylated interferon is the only approved drug class that has been proven beneficial. The treatment regimen is usually once weekly for at least one year. Orthotopic liver transplantation has also shown value for the treatment of fulminant acute and advanced chronic hepatitis D infections.

Sources:

- https://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/hdv/index.htm

- http://www.hepb.org/research-and-programs/hepdeltaconnect/symptoms

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK470436

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5580405

- https://web.stanford.edu/group/virus/delta/2008/Pathogenesis.html

- https://web.stanford.edu/group/virus/delta/2008/Clinical.html

- https://web.stanford.edu/group/virus/delta/2005/#epidemiology

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4208707/

- http://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/hepatitis-d

0Comments